Discovering a Treasure

After transitioning from Missouri to San Francisco, where I lived for 5 years, I moved to Colorado. Traveling, hiking and camping in Colorado with my family in the 50’s and 60’s, I fell in love with the mountains, landscape and climate. I always knew I would find my way to Colorado.

It didn’t take long before I became a guest lecturer on the adjunct faculty at Denver University. One night, in 1995, when I was teaching a class of adult MBA students, we got into a meaningful discussion about “balance of life”. We talked about the importance, the need to rejuvenate ourselves in our free time by engaging in things we enjoy and are passionate about. Afterwards, one of the students asked me, “You asked us about what we enjoy that recharges our batteries, what about you? What are you passionate about?” I told him about my interest in Native Americans, their culture, and my appreciation for the photographs of Edward Curtis. He responded, “Well you know, we have some Curtis photographs here at the university, in the special collections library downstairs.” I said, “Really!? Cool, I’ll check it out. Thanks.”

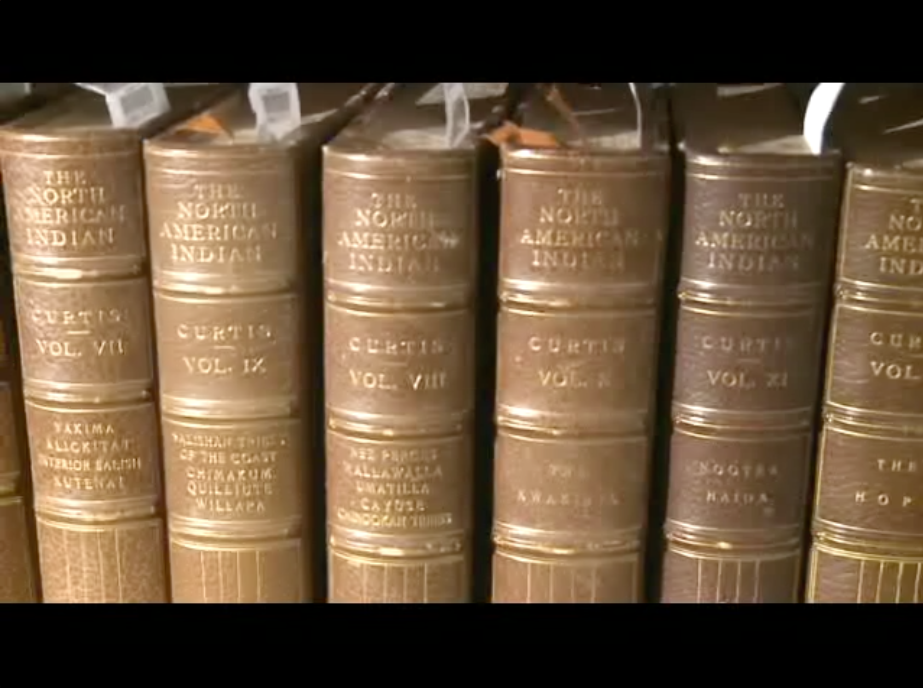

Three months later, I went to the special collections library and asked the curator, Steve Fisher, if they had some Curtis photographs there. He said, “Yes we do, but we’re really busy right now. Why don’t you come back at winter break?” Three more months passed. I made an appointment with the curator to see what they had. It was the middle of December. Steve Fisher escorted me downstairs to the vault. It was eerily dimly lit, empty and quiet with all the students and staff gone. He brought me to the high security doors protecting the valuable contents residing in the climate controlled vault. He had me look away as he pushed the numbered buttons entering the code to open the vault. The shelves, ladened with rare old books and manuscripts, were mounted on rollers and glided sideways apart allowing us access to the aisle with the Curtis prints. In the dim light, I peered to the back of the aisle and saw the glint of the gold leaf lettering embossed on the Moroccan leather folios and text books. In that moment I realized we didn’t have “some” Curtis photographs; we had all 20 folios and all 20 books! We had a complete, intact, 20-volume set of Curtis’s master work, “The North American Indian”

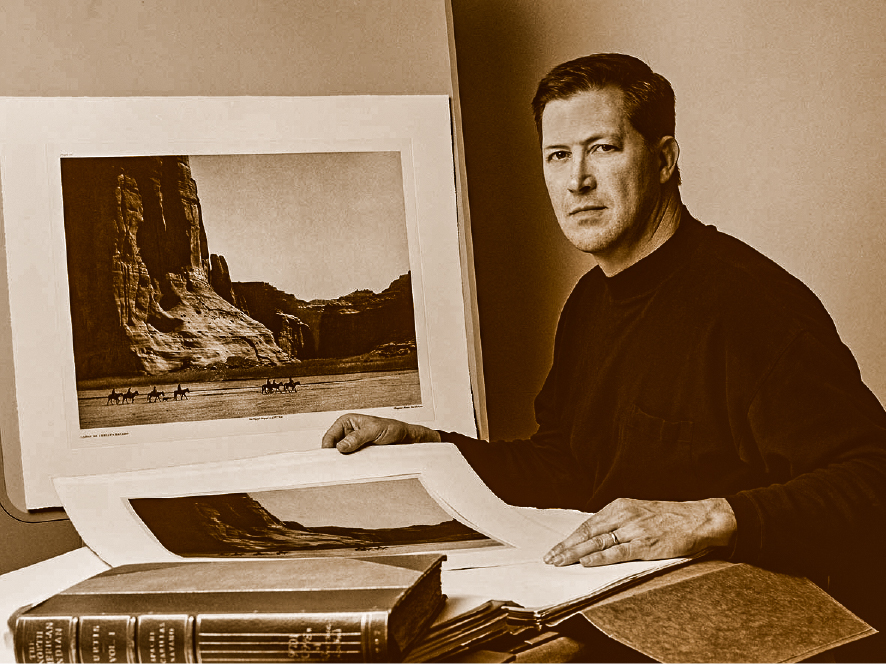

The curator asked what I would like to see first. I said, “Folio number I, the Navaho and the Apache”. We lifted Folio I off the shelf and took it to the viewing room. Following the protocol, I put on the white cotton gloves and he left the room locking the door. I opened the folio and started going through the large folio prints one by one. After all the visits I’ve had over the years to museums and libraries around the country, requesting to see their Curtis collections, and in some cases being denied or kicked out after I was apparently overly persistent, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. They were all printed on the fine Japanese tissue paper, considered by many collectors as the most preferred because of their unique magical sense of light and depth. As I approached and came to Plate 28, “Canon De Chelly”, tears started to well up in my eyes. I had to back away from the table so my tears wouldn’t fall on these rare invaluable prints.

I had been teaching at the university since 1985. And literally, right under my nose, under my feet, downstairs below resided something I had been studying and seeking most of my adult life. Curtis’s Magnus Opus had been very well preserved, right here, in arid Colorado, all this time since 1938 in our climate controlled vault. No humidity, no sunlight, nobody touching them with their oily fingers. I realized I was looking at the best set of Curtis’s photogravures I had ever seen. A uniquely American treasure.