Getting Exclusive Rights

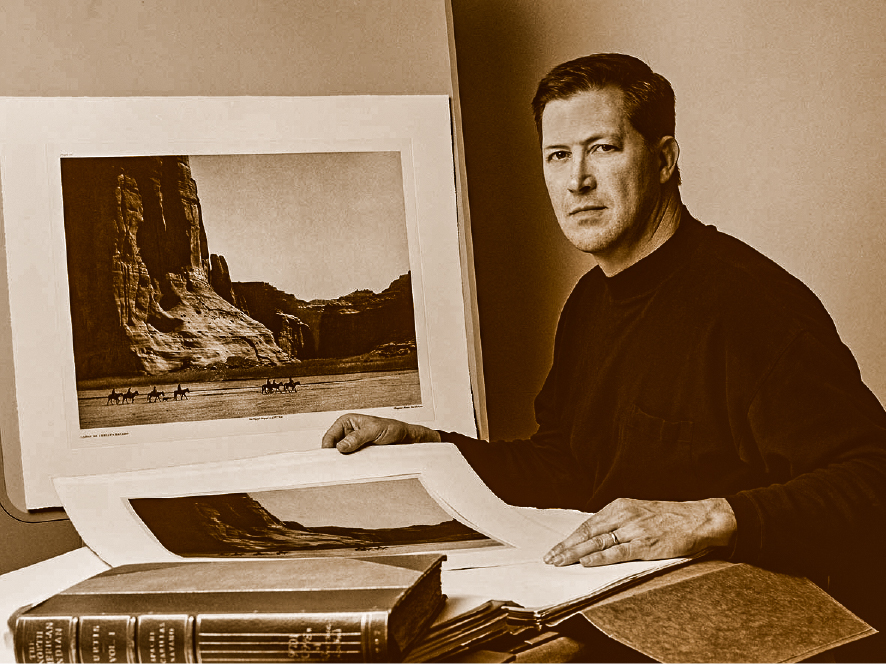

After discovering the beautiful complete set of Curtis’s original photographs contained in “The North American Indian” here at Denver University’s special collections library, I thought these wonderful examples of Curtis’s work should be shared with more people. They had been in our vault since 1938. It was time for other people who appreciate Curtis’s photographs, or those who had never seen them before, to see these.

Most of the complete sets of original vintage prints are held in museums, private libraries and collections that are not accessible to the public. Some can be seen in a few high end galleries, but the prices of the vintage prints are prohibitive for most people. I talked with the curator, Steve Fisher, about my idea, my desire to share these great, historically important, high quality photographs with a wider audience. I approached him with the proposition that it would be a good project to produce high quality prints, better than those mediocre prints and posters found in museum gift shops and on line, and to offer them at an affordable price. He was immediately hesitant, and not inclined to grant permission for me, or anyone else, to reproduce the originals in his charge. Based on past experience, I expected such a response

Over the years, I have made many attempts to get permission to see Curtis’s originals at several museums and libraries across the country. Repeatedly, I was denied access. In one particular instance, I confirmed there was a complete set of the “North American Indian” in the Western Art wing of a certain public library that will remain unnamed for now. I managed to convince the librarian there to let me see their set of vintage photogravures. We followed all the appropriate steps of their protocol; wearing acid free cotton gloves, restricted to the viewing room, door locked, security guard outside the door able to observe through the large window. I could immediately tell these photogravures were printed on the Van Gelder paper from Holland, but in pretty poor condition. They obviously had not been taken good care of. Still I was enjoying them. I was only in there a few minutes when the head curator burst into the room and put an abrupt stop to my viewing session. I said that I had asked permission and we were doing everything properly. She said she had not been told and did not give permission. This was an example of what can happen when you don’t ask, “Mother may I?” I hope the librarian and security guard didn’t get into too much trouble.

Not being one easily discouraged, especially when there is a cause I deem worthy, I was not ready to give up on the Denver University collection. These originals were so beautiful. They just had to be seen by the public. I kept approaching the curator and others at the University about various arrangements that would make it a mutually beneficial project. Finally, a year later, after a lot of begging and pleading on my part, I received a call from the curator saying, “Can you come in to meet with us tomorrow? We’re going to make your day.” I was elated.

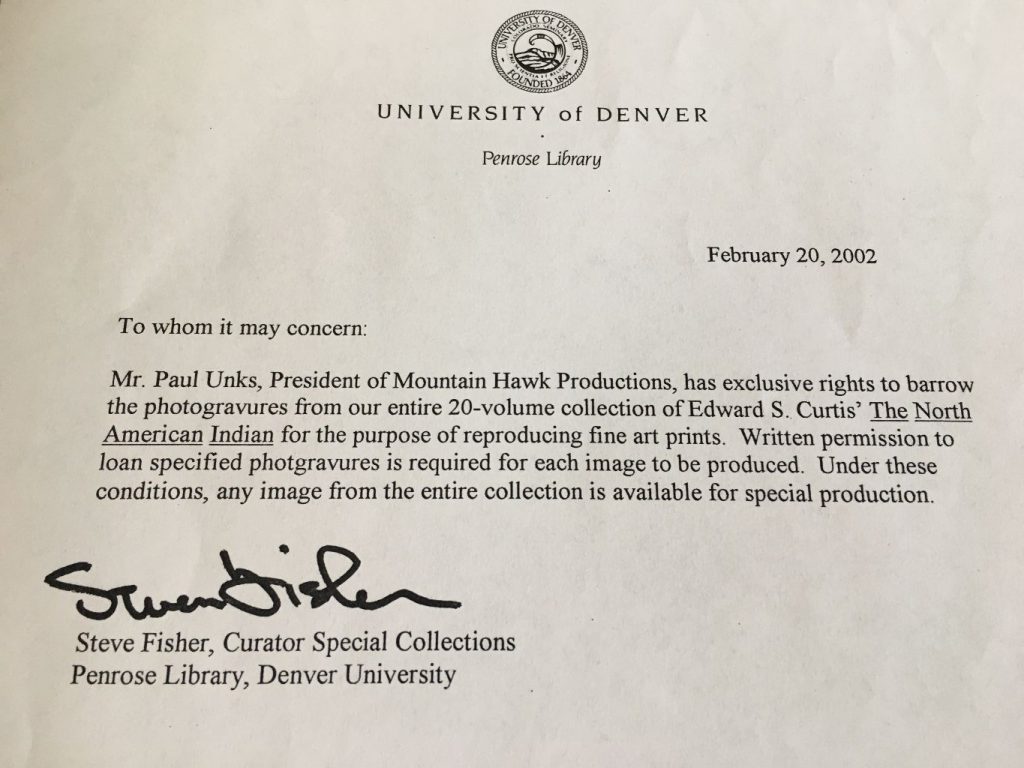

The next day we met and reached an agreement granting me exclusive rights to the University’s originals. Under the condition that I make prints only for me, not for the public, and that the prints be made in a manner faithful to Curtis’s artistic standard. The curator said, “Let’s see if you can do this. Then maybe we’ll see about maybe making them available to the public.” I rushed home like a little kid with our written agreement to show my wife. It was like a scene from “Jack and the Bean Stalk”. There I was, all lit up with excitement, with the “beans” in my hand. My wife, the pragmatic realist, simply said, “How much is this going to cost?” I said, “I don’t know, but isn’t this great?!”