Paul Unks of Mountain Hawk restores and resurrects the beautiful images captured by Edward Curtis of the Native American’s in the 1800s. This story is a feature by Colorado’s NBC 9 News that highlights Paul’s dedication to the craft and sharing our cultures’ ancestry.

Category: Paul Unks

An Unexpected Catalyst for the Rejuvenation of Creativity

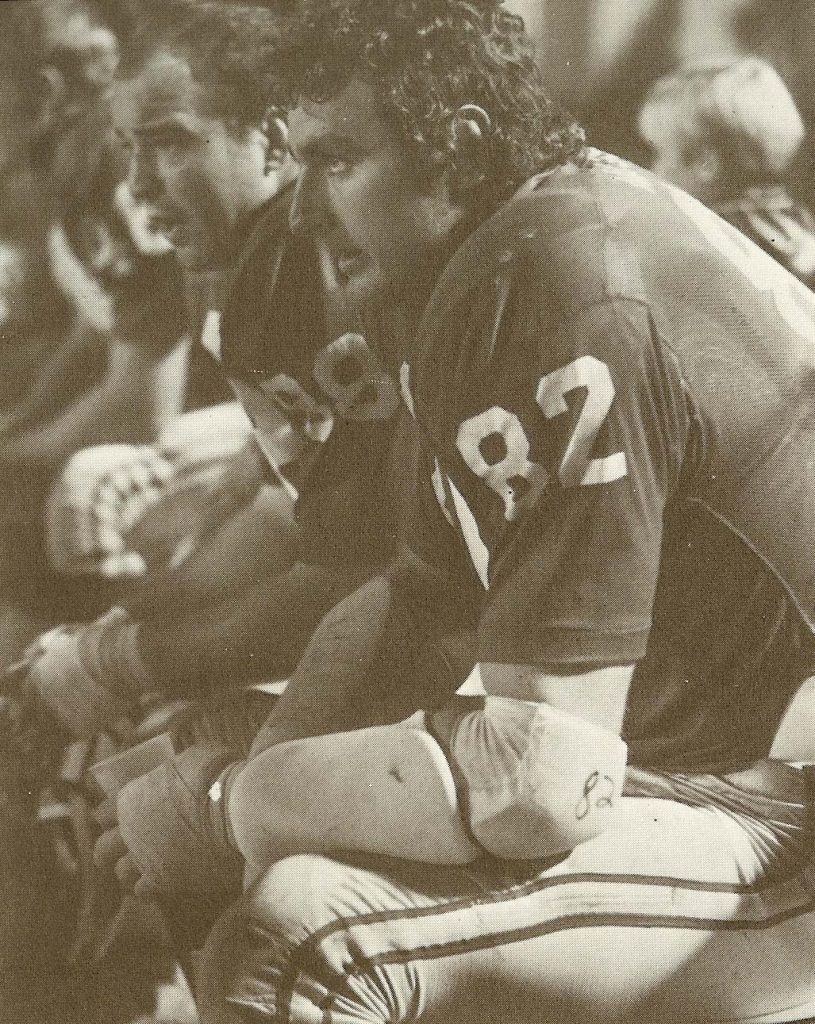

For years growing up in St. Louis, I dreamt of playing football at the University of Missouri. I wanted to be their quarterback. All three of my older brothers went to Mizzou, one of whom played football. During visits to Columbia, my brothers introduced me to some of the great all American and future pro players I admired so much like Johnny Roland, Mel Gray, Roger Wehrli, Joe Moore, James Harrison, Mike Bennett and future successful head coach Gary Barnett, as well as quarterback Terry McMillan who was so nice and encouraging to me. My brothers and I made the long road trip in the old family station wagon to New Orleans to see Missouri play in the Sugar Bowl against Florida led by Heisman Trophy winner and Hall of Famer Steve Spurrier. When I graduated from high school and it came my turn to go to the big university in COMO (Columbia, MO), I was very excited and motivated.

I worked very hard that summer doing my best to prepare for the challenge of playing at the collegiate level. Dan Devine was the head coach at the time. Being one the three smallest guys on the team, I knew I had to work harder and compensate somehow by being as fit, strong and fast as I could be, as well as throw the ball better. I got to the point where I could consistently hit the receivers on the numbers at 50 to 60 yards downfield. Things were going well. Within 2 weeks I made first string on the freshman team. One of my team mates was John Matuszak. “The Tooz”, as he was called, was 6’9”, 300 pounds, ripped and quick as a cat. Unfortunately, he occasionally had difficulty controlling his aggression. One day in scrimmage, from the blind side, he sacked me very hard, landing me on my shoulder separating me from my throwing arm. The team doctor told me, “You’re not going to be a quarterback anymore, at least not a right handed quarterback.”

Like any young person losing their “dream”, I was devastated. Some of my friends stopped being my friends, now that I wasn’t “the quarterback” anymore. I remember some nights, walking through campus by myself, crying and wondering what I was going to do. I went through a time of depression. My present and future was unclear, uncertain. I was confused and scared.

Surprisingly, I received some unexpected help and support from our assistant coach, Prentice Gautt. My dad and brothers had season tickets to the St. Louis Football Cardinals games where we saw Prentice Gautt play many times. He ran like a deer and was tough as nails. He was the first black football player on scholarship at the University of Oklahoma, and the leading rushing gainer. He grew up in the south, where as a black man, he experienced prejudice. But somehow, he didn’t become bitter or angry. He found a way to transcend irrational hatred and unfair treatment. After retiring from pro ball, he became our backfield coach at Mizzou. Little did I know he was also getting his Ph.D. in counseling psychology. He knew I was struggling and feeling lost. For some reason, he saw something in me and decided to become a mentor to me. He said, “I see your leadership, that you care about the guys on the team, and they know you care. I think you have a health inducing personality. You have a way of visualizing, seeing the field, play making and communicating that is very creative.” I responded with, “What?” He paused and then asked, “Have you thought of doing something in these areas? I think you would be good at, and enjoy something there. You could explore it.” He had held the mirror up, reflecting back to me he saw a strong creative drive and desire to help others. He was the first older man in my sports world to see something of value in me other than athletic potential.

Oklahoma Historical Society – GAUTT, PRENTICE (1938- 2005) https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=GA023

I decided to reengage in a couple of my passions, music and photography, and start experiencing and “exploring”. I home to St Louis, where I played violin and piano for 4 years each, and also enjoyed photography with my dad. I picked up my violin and the single lens reflex camera my dad got me and brought them both back to Columbia. I started going on long walks with my camera and a friend’s dog exploring nature and local subject matter. I moved out of the main fraternity house to the annex and would sometimes play my violin in the cavernous bath and shower room because it had such good acoustics. While I’m sure a lot of the guys found it annoying, one of the guys, Mike Flemming heard me playing and asked if I would like to play together with him and one of his musician buddies sometime. I said, “Sure!”

My new music friends taught me some fiddle tunes to play together. I really enjoyed it. Before too long, I found myself transitioning from my classical violin background to folk and bluegrass fiddle. I realized I had been recruited to become a new member of a folk/rock bluegrass band. We became known as “The Hell Band” and played together for the next few years. At our zenith, we were the warm up act for the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, a little bit better known band with a cooler name, and also from the Missouri Ozark region. I got tired of the musician life style staying up all night playin, and decided to go to graduate school. My two buddies, Mike Flemming and Mike Henderson stuck with it, moved to Nashville, persevered for years and formed a band called “The Steel Drivers”. Chris Stapleton was their lead singer. They won a Grammy for best bluegrass album in 2016.

It was during this time I started going to photojournalism school. I liked the classes and the professors, some of whom worked at National Geographic. I enjoyed the comradery of writers, reporters, journalists and photographers. And I really enjoyed working in the lab making high quality black and white silver gelatin photographic prints in the dark room with the low red light and the smell of the chemicals in the developer bath. I appreciated having access to all these terrific people and resources. How different it was now compared to making rudimentary black and white prints with my dad in our basement with an enlarger we fashioned out of a coffee can. But those are great memories too, all part of the journey leading up to learning so much from the best. I got to take things to a whole new level. I had the opportunity to work at the Columbia Missourian newspaper collaborating with writers on editorial human interest stories. As a result, some of my photographs were published in a few newspapers and magazines.

A big discovery came when one of my professors helped me to appreciate the quality and importance Edward Curtis’s work. I remember seeing his magnificent sepia tone photographs for the first time. I couldn’t believe the quality of these historic photographic prints he was able to achieve with his old large cumbersome wooden box camera on a tripod and glass plate negatives, with no shudder speeds or aperture settings. And when I learned he wrote 20 books to go with his photographs, I realized Curtis was the first to use his camera and words to chronicle a great endangered culture and history, and do so with artistic beauty. He was the quintessential National Geographic photojournalist before there was a National Geographic. He was a landmark photographer, the most important photographer of 19th century western America. What an inspiration he was and is still is for me. And thus began my odyssey with Edward Curtis.

In retrospect, I realized getting injured was the catalyst for me getting off a path that was not so good for me and led to a better more meaningful and fulfilling path. Sports, particularly at the higher levels, tend to foster a self – centeredness I think. At least for me, I realized I was increasingly taking on a self-centered perspective. I can only imagine, and shudder to think what would have become of me had I realized my “dream” of being a star quarterback. Because of the career ending injury, losing my old sports life and going through the subsequent difficult transition, and being blessed with good people supporting me, I became more aware, other-centered, more compassionate, and able to develop my creative side. I found my people who shared and fed each other’s intellectual curiosity and creative expression. I had been done a favor I didn’t ask for. Unwillingly, I was taken off an unhealthy path and shepherded onto a much better, satisfying and sustainable path. That’s something for which I am very thankful.

Post Script

After a pattern of losing control and getting into trouble on and off the field, John Matuszak was kicked off the team by the head coach. The “Tooz” went to the University of Tampa where he became an all American and was the NFL number one draft pick. He played with the Oakland Raiders where he was very good fit with that culture, became an all pro defensive tackle feared by other players, won 2 super bowls and acted in a few Hollywood movies. John used to say, “NFL stands for Not For Long”. He died 3 years after retiring from the Raiders at age 38. I was bitter at the time back in 1971, but eventually decided it was better to practice forgiveness and gratitude. RIP John.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Matuszak

https://www.rockmnation.com/2013/1/12/3870616/well-tooz-we-hardly-knew-you

https://bobleesays.com/2014/09/17/could-the-tooz-date-your-sister/

There have been a few times when I was convinced I wanted something very badly and I didn’t get it, and then I came to learn what an awful thing I was saved from, and what a blessing I found instead.

“Remember that not getting what you want is sometimes a wonderful stroke of luck.”

– The Dalai Lama –

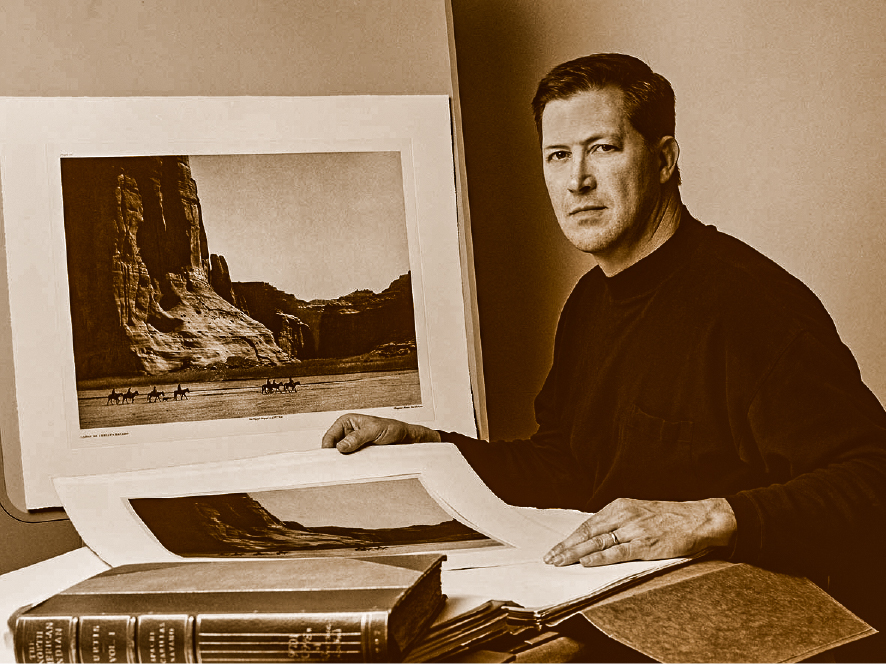

Getting Exclusive Rights

After discovering the beautiful complete set of Curtis’s original photographs contained in “The North American Indian” here at Denver University’s special collections library, I thought these wonderful examples of Curtis’s work should be shared with more people. They had been in our vault since 1938. It was time for other people who appreciate Curtis’s photographs, or those who had never seen them before, to see these.

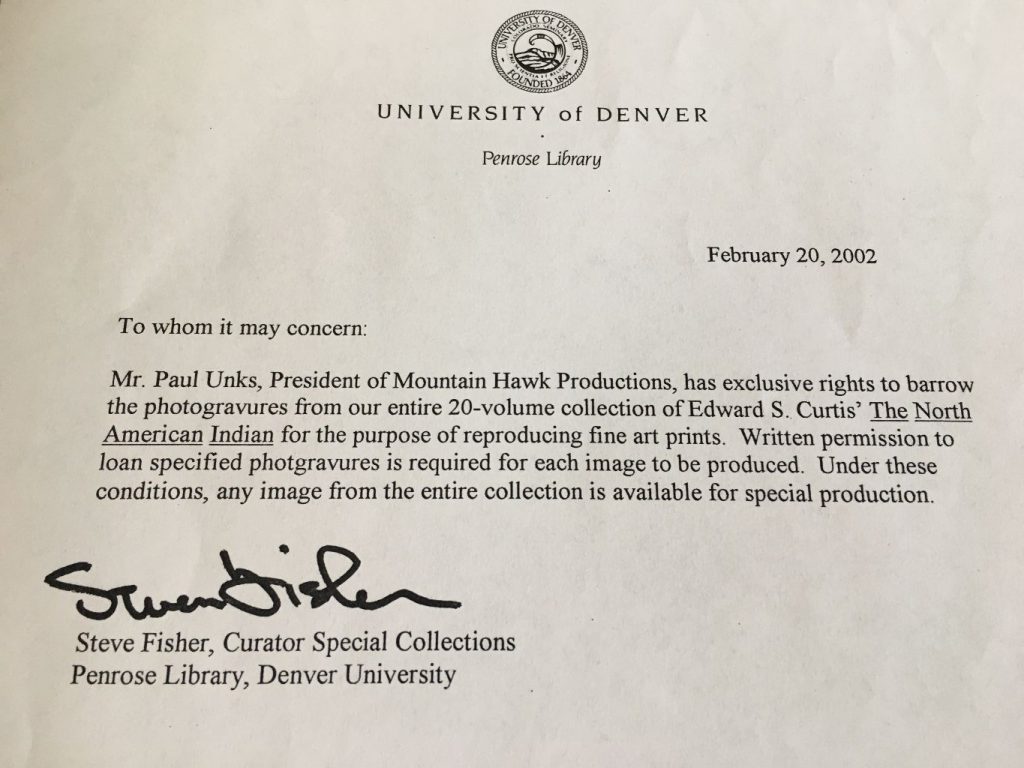

Most of the complete sets of original vintage prints are held in museums, private libraries and collections that are not accessible to the public. Some can be seen in a few high end galleries, but the prices of the vintage prints are prohibitive for most people. I talked with the curator, Steve Fisher, about my idea, my desire to share these great, historically important, high quality photographs with a wider audience. I approached him with the proposition that it would be a good project to produce high quality prints, better than those mediocre prints and posters found in museum gift shops and on line, and to offer them at an affordable price. He was immediately hesitant, and not inclined to grant permission for me, or anyone else, to reproduce the originals in his charge. Based on past experience, I expected such a response

Over the years, I have made many attempts to get permission to see Curtis’s originals at several museums and libraries across the country. Repeatedly, I was denied access. In one particular instance, I confirmed there was a complete set of the “North American Indian” in the Western Art wing of a certain public library that will remain unnamed for now. I managed to convince the librarian there to let me see their set of vintage photogravures. We followed all the appropriate steps of their protocol; wearing acid free cotton gloves, restricted to the viewing room, door locked, security guard outside the door able to observe through the large window. I could immediately tell these photogravures were printed on the Van Gelder paper from Holland, but in pretty poor condition. They obviously had not been taken good care of. Still I was enjoying them. I was only in there a few minutes when the head curator burst into the room and put an abrupt stop to my viewing session. I said that I had asked permission and we were doing everything properly. She said she had not been told and did not give permission. This was an example of what can happen when you don’t ask, “Mother may I?” I hope the librarian and security guard didn’t get into too much trouble.

Not being one easily discouraged, especially when there is a cause I deem worthy, I was not ready to give up on the Denver University collection. These originals were so beautiful. They just had to be seen by the public. I kept approaching the curator and others at the University about various arrangements that would make it a mutually beneficial project. Finally, a year later, after a lot of begging and pleading on my part, I received a call from the curator saying, “Can you come in to meet with us tomorrow? We’re going to make your day.” I was elated.

The next day we met and reached an agreement granting me exclusive rights to the University’s originals. Under the condition that I make prints only for me, not for the public, and that the prints be made in a manner faithful to Curtis’s artistic standard. The curator said, “Let’s see if you can do this. Then maybe we’ll see about maybe making them available to the public.” I rushed home like a little kid with our written agreement to show my wife. It was like a scene from “Jack and the Bean Stalk”. There I was, all lit up with excitement, with the “beans” in my hand. My wife, the pragmatic realist, simply said, “How much is this going to cost?” I said, “I don’t know, but isn’t this great?!”

Discovering a Treasure

After transitioning from Missouri to San Francisco, where I lived for 5 years, I moved to Colorado. Traveling, hiking and camping in Colorado with my family in the 50’s and 60’s, I fell in love with the mountains, landscape and climate. I always knew I would find my way to Colorado.

It didn’t take long before I became a guest lecturer on the adjunct faculty at Denver University. One night, in 1995, when I was teaching a class of adult MBA students, we got into a meaningful discussion about “balance of life”. We talked about the importance, the need to rejuvenate ourselves in our free time by engaging in things we enjoy and are passionate about. Afterwards, one of the students asked me, “You asked us about what we enjoy that recharges our batteries, what about you? What are you passionate about?” I told him about my interest in Native Americans, their culture, and my appreciation for the photographs of Edward Curtis. He responded, “Well you know, we have some Curtis photographs here at the university, in the special collections library downstairs.” I said, “Really!? Cool, I’ll check it out. Thanks.”

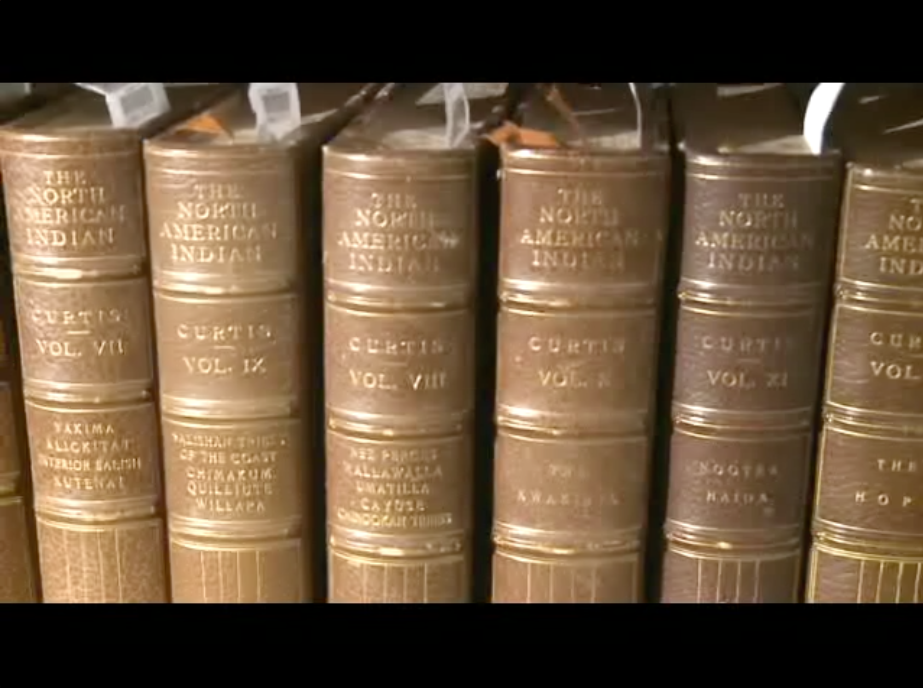

Three months later, I went to the special collections library and asked the curator, Steve Fisher, if they had some Curtis photographs there. He said, “Yes we do, but we’re really busy right now. Why don’t you come back at winter break?” Three more months passed. I made an appointment with the curator to see what they had. It was the middle of December. Steve Fisher escorted me downstairs to the vault. It was eerily dimly lit, empty and quiet with all the students and staff gone. He brought me to the high security doors protecting the valuable contents residing in the climate controlled vault. He had me look away as he pushed the numbered buttons entering the code to open the vault. The shelves, ladened with rare old books and manuscripts, were mounted on rollers and glided sideways apart allowing us access to the aisle with the Curtis prints. In the dim light, I peered to the back of the aisle and saw the glint of the gold leaf lettering embossed on the Moroccan leather folios and text books. In that moment I realized we didn’t have “some” Curtis photographs; we had all 20 folios and all 20 books! We had a complete, intact, 20-volume set of Curtis’s master work, “The North American Indian”

The curator asked what I would like to see first. I said, “Folio number I, the Navaho and the Apache”. We lifted Folio I off the shelf and took it to the viewing room. Following the protocol, I put on the white cotton gloves and he left the room locking the door. I opened the folio and started going through the large folio prints one by one. After all the visits I’ve had over the years to museums and libraries around the country, requesting to see their Curtis collections, and in some cases being denied or kicked out after I was apparently overly persistent, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. They were all printed on the fine Japanese tissue paper, considered by many collectors as the most preferred because of their unique magical sense of light and depth. As I approached and came to Plate 28, “Canon De Chelly”, tears started to well up in my eyes. I had to back away from the table so my tears wouldn’t fall on these rare invaluable prints.

I had been teaching at the university since 1985. And literally, right under my nose, under my feet, downstairs below resided something I had been studying and seeking most of my adult life. Curtis’s Magnus Opus had been very well preserved, right here, in arid Colorado, all this time since 1938 in our climate controlled vault. No humidity, no sunlight, nobody touching them with their oily fingers. I realized I was looking at the best set of Curtis’s photogravures I had ever seen. A uniquely American treasure.