Paul Unks of Mountain Hawk restores and resurrects the beautiful images captured by Edward Curtis of the Native American’s in the 1800s. This story is a feature by Colorado’s NBC 9 News that highlights Paul’s dedication to the craft and sharing our cultures’ ancestry.

Category: Edward Curtis

The Beauty Is In The Details

Mountain Hawk Pigmented Ink Prints

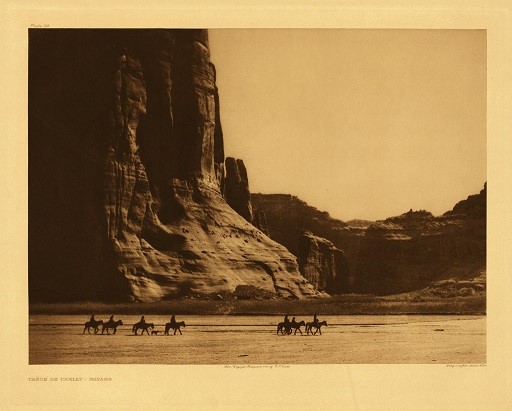

Pigmented ink prints, or giclées as they are more commonly known, are made using a digital technique. An original work of art — in our case an Edward Curtis photograph — is scanned at extremely high resolution and the image printed on heavy top quality paper.

Fine art digital printers were originally designed to reproduce colorful oil and watercolor paintings. We learned that it is much more difficult to achieve the full range of sepia tones in a photogravure than to print the multiple colors of a painting, particularly when it comes to the fine distinction of dark shadow detail. To obtain the authentic look of a vintage photograph, we invested $85,000 in a state-of-the-art digital fine art printer, and then modified its software to apply 30 different shades of sepia tone ink. This allows us to reproduce every tone in a Curtis print — from near black and to medium brown to white highlights.

We custom make an exclusive mixture of seven sepia tone inks that, once properly combined, create a wonderful richness and sense of light. The inks are stable up to 120 years giving the pigmented ink prints a very respectable archival rating.

Our pigmented ink giclées are printed on 100% cotton watercolor paper imported from Somerset, England. This special paper has a rich texture and smooth surface that absorbs ink without blurring, allowing us to maintain high resolution and fine distinctions in our beautiful prints.

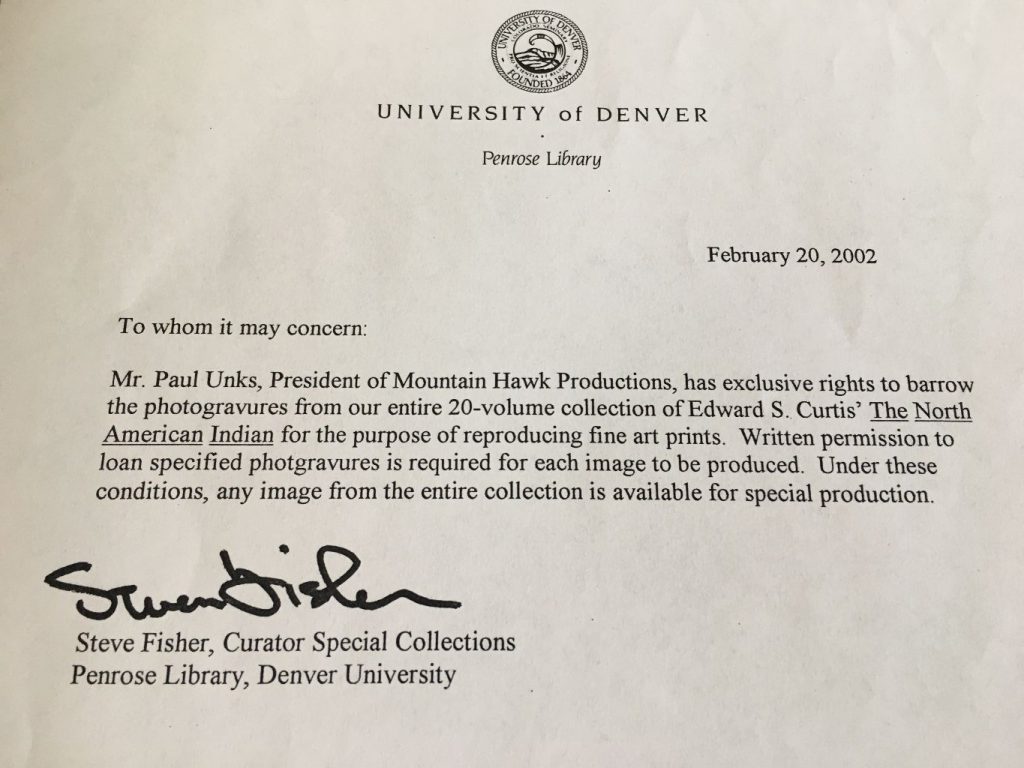

Getting Exclusive Rights

After discovering the beautiful complete set of Curtis’s original photographs contained in “The North American Indian” here at Denver University’s special collections library, I thought these wonderful examples of Curtis’s work should be shared with more people. They had been in our vault since 1938. It was time for other people who appreciate Curtis’s photographs, or those who had never seen them before, to see these.

Most of the complete sets of original vintage prints are held in museums, private libraries and collections that are not accessible to the public. Some can be seen in a few high end galleries, but the prices of the vintage prints are prohibitive for most people. I talked with the curator, Steve Fisher, about my idea, my desire to share these great, historically important, high quality photographs with a wider audience. I approached him with the proposition that it would be a good project to produce high quality prints, better than those mediocre prints and posters found in museum gift shops and on line, and to offer them at an affordable price. He was immediately hesitant, and not inclined to grant permission for me, or anyone else, to reproduce the originals in his charge. Based on past experience, I expected such a response

Over the years, I have made many attempts to get permission to see Curtis’s originals at several museums and libraries across the country. Repeatedly, I was denied access. In one particular instance, I confirmed there was a complete set of the “North American Indian” in the Western Art wing of a certain public library that will remain unnamed for now. I managed to convince the librarian there to let me see their set of vintage photogravures. We followed all the appropriate steps of their protocol; wearing acid free cotton gloves, restricted to the viewing room, door locked, security guard outside the door able to observe through the large window. I could immediately tell these photogravures were printed on the Van Gelder paper from Holland, but in pretty poor condition. They obviously had not been taken good care of. Still I was enjoying them. I was only in there a few minutes when the head curator burst into the room and put an abrupt stop to my viewing session. I said that I had asked permission and we were doing everything properly. She said she had not been told and did not give permission. This was an example of what can happen when you don’t ask, “Mother may I?” I hope the librarian and security guard didn’t get into too much trouble.

Not being one easily discouraged, especially when there is a cause I deem worthy, I was not ready to give up on the Denver University collection. These originals were so beautiful. They just had to be seen by the public. I kept approaching the curator and others at the University about various arrangements that would make it a mutually beneficial project. Finally, a year later, after a lot of begging and pleading on my part, I received a call from the curator saying, “Can you come in to meet with us tomorrow? We’re going to make your day.” I was elated.

The next day we met and reached an agreement granting me exclusive rights to the University’s originals. Under the condition that I make prints only for me, not for the public, and that the prints be made in a manner faithful to Curtis’s artistic standard. The curator said, “Let’s see if you can do this. Then maybe we’ll see about maybe making them available to the public.” I rushed home like a little kid with our written agreement to show my wife. It was like a scene from “Jack and the Bean Stalk”. There I was, all lit up with excitement, with the “beans” in my hand. My wife, the pragmatic realist, simply said, “How much is this going to cost?” I said, “I don’t know, but isn’t this great?!”

Genesis

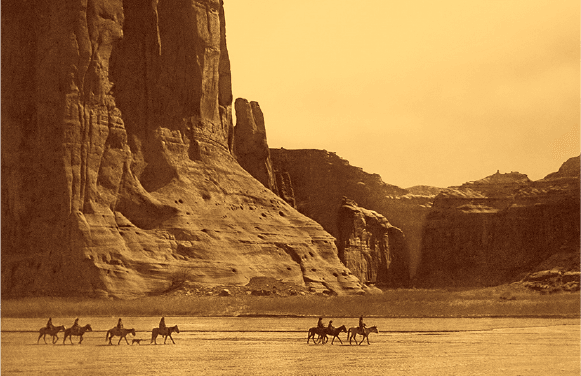

Folio I, Plate 28, Canon De Chelly ~ Navaho

– E. S. Curtis –

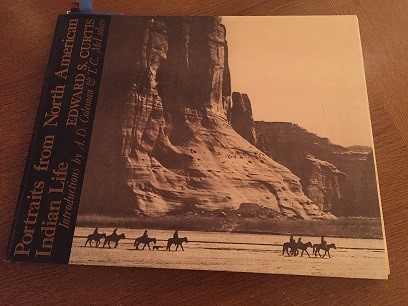

“Canon De Chelly” is one of my favorite photographs of all time. I first saw it in 1972 when I was a young photojournalism student at the University of Missouri. I thought to myself, “Wow, I didn’t know these kinds of photographs existed, combining the culture of a great people, their land and history, and doing it so artistically. Who is this guy, Edward Curtis?” I realized I was looking at the first National Geographic type of photography, made before there was a National Geographic! No wonder my 2 favorite professors, Dr. Art Terry; former editor in chief of National Geographic Magazine, and Angus McDougall encouraged me to check out the work of Edward Curtis.

This experience inspired my long standing interest and study of Edward Curtis’s prints and the Native Americans. I was struck by its wonderful sense of light, depth and composition. I was amazed Curtis could get such a great result with that old cumbersome large format camera on a tripod with the glass plate negatives. This, and many other Curtis photographs, reminds me of the master English, Dutch and Italian painters. It was the catalyst that led me to seek out and explore Curtis’s entire body of work.

Coleman & McLuhan 1972

During my early days working in the photojournalism school’s dark room, I was moving from making color photographs to falling in love with making black and white silver gelatin prints. Later, I was to make another shift. I was developing a passion for sepia tone ink prints on paper, known as photogravures.

Little did I know that 25 years later I would make another great “discovery” when I found a complete mint conditioned 20-volume set of Curtis’s original photogravures contained in his Magnus opus, “The North American Indian” curated at Denver University where I had been a guest lecturer since 1985.

I would also be fortunate enough to eventually meet and get to know some of the descendants of the Navaho riders seen in “Canon De Chelly”. But these are stories to be shared another time.

~ Paul Unks, Mountain Hawk ~